Powerful Estate Planning Opportunities for Clients With Carried Interest. Originally published in Trust & Estates

Carried interest (carry) refers to the profits interest that a fund's general partners (GPs) receive in addition to their direct interest and management fee. In many funds, the carry is a significant part of the partner’s compensation. With the elevated exemption expected to sunset at the end of 2025, now is an ideal time for estate planning when it comes to your client’s valuable carried interest.

Real World Example

John is a successful private equity fund manager who would like to fund a trust for his young children. His kids won’t have access to the assets for the next 10 years. John could fund the trust with cash or marketability securities. However, with that approach he would pay a significant gift tax or be forced to use up a large portion of his lifetime exemption relative to the size of the gifts. Either way, John would be accomplishing the goal of funding his children’s trust but would be doing so in an inefficient manner.

Alternatively, John could fund the trust with a portion of his GP interest in a newly formed fund. His carry could be included in the gift. The carry might have significant value in 10 years, but it’s currently worth much less. By gifting his GP interest including the carry, John could accomplish his gift with little to no gift tax and move a potentially high appreciating asset out of his taxable estate in an efficient manner.

Gifts made from an individual’s estate use exemption (or incur gift tax if no exemption remains) based on their fair market value (FMV) at the date of transfer. Therefore, assets with a high potential for appreciation are ideal for estate planning. By gifting an asset that’s expected to increase in value, your client can effectively transfer more wealth to their heirs while using less of their lifetime estate tax exemption. This is referred to as “exemption leveraging,” in which strategic gifting can effectively expand assets protected above the exemption amount. It’s also where carry comes into play. A carry at time zero of a fund has a low value relative to its full potential. This is due to the risk that the fund has to return capital to investors and fails to exceed the promised hurdle.

The carry is never worth $0. While it may seem counterintuitive, even a carried interest in a fund that has made no investments and that hasn’t even called a dollar of capital, is worth more than $0. Additionally, the Internal Revenue Service doesn’t accept $0 FMVs, and risk mitigation is an essential component of any estate planning. Naturally, the next question is, “What is it worth?”

Risk of a Bad Appraisal

Unfortunately, not all appraisals are the same. In order to perform an appraisal of a carried interest, the appraiser needs an in-depth understanding of fund structures, cash flows and risks. A bad appraisal can cost a taxpayer dearly. Poor methodology and support can expose your client to IRS audit risk, penalties and interest. Additionally, an overvalued asset is money directly out of your client’s pocket. It’s essential to use a qualified appraiser accustomed to working with clients who receive carried interest compensation.

Several methodologies can be used to determine value. By definition, a profits interest is out-of-the-money, so logically an option pricing model (OPM) could be considered. A Black-Scholes model requires many inputs. The issues arise when you start trying to enter the inputs into the model.

Key Considerations

What’s the stock price of a carried interest? Perhaps committed capital could be used as a placeholder, but what’s the strike? How do we factor in the idiosyncrasies of the limited partnership agreement (LPA) and how the distributions are paid out via the capital waterfall? If the term used is the term of the fund, does that clash with the fact that it will distribute capital and wind down throughout the harvest period? How do we benchmark volatility? Are big public private equity firms like Apollo, Ares or KKR a good comparison for a single fund?

Funds are complex organisms with a specific lifecycle and hundreds of pages of governing documents that require technical expertise to understand. Thus, an option pricing model can’t appropriately capture the FMV of a carry. Given the need for discrete projections of fund and partner-level cash flows, a discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis makes sense. The DCF allows you to map a fund’s full lifecycle through investment, harvest and extension periods while tracking initial investments, follow-ons and exits. The DCF can explicitly build a roadmap to return of capital, achievement of the hurdle and payment of carry. By incorporating the LPA, historic prior fund performance and market data, the DCF presents a comprehensive analysis that dials in exactly to the date of transfer.

OPM vs DCF Calculation Comparison

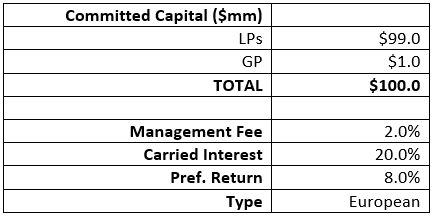

Let’s describe a simple fund structure and the implied value under an OPM and a DCF. See table below regarding fund structure.

Let’s assume the fund makes investments ratably over a five-year investment period and returns a 2.0x exit multiple over a four-year holding period (19% gross IRR). The fund has a life of 10 years with a possible additional two years of extension. Let’s assume our valuation date is Day One of the fund’s life.

Source: DeJoy & Co. Advisors & CPAs, 2023

Using an OPM, how do we estimate a reasonable stock price and strike price? To start, the capital commitment may be a good proxy for the stock price, so we can fill in $100 million. However, that also operates under the assumption that all capital is deployed, which likely won’t be true until Year 5 of the fund.

Now it gets even more complicated. The carry is “out-of-the-money" by definition, but what’s the hurdle or strike price? We could project LP capital plus a preferred return (plus GP capital), but we need a specific term over which to accumulate the preferred return. So put a hold on that and let’s talk term, which is the most challenging input to nail down and the most sensitive. A few possibilities are: (a) the life of the fund until termination; (b) life of the fund until the final extension; or (c) the average investment holding period. Therefore, our term could be anywhere from four years to twelve years and our accumulated preferred return could be $136 million to $250 million.

The next challenge is estimating volatility. We have a sample of publicly traded PE firms, but those represent collective GP, LP, and management companies across a range of funds at a myriad of stages. Estimating that could entail using an average of observed volatilities for those publicly traded funds or adding on a significant premium for lack of diversification of the fund – perhaps 30% to 50%. So, what’s the value of the carry using an OPM? Roughly $4 million to $10 million. That’s right, it’s a huge range. That’s why OPM is problematic. Strike price, term and volatility are very hard to nail down. Also, OPM doesn’t have the granularity to be sensitive to the finer points of the LPA.

Conversely, armed with an understanding of PE fund structure, a copy of the LPA and the assumptions outlined above, I can tell you exactly what a projected fund cash flow structure looks like. I can tell you that the fund’s gross exit multiple of 2.0x looks like 1.7x net of management fees and fund expenses with a 14% net IRR. I can tell you that LPs are projected to receive a 13% IRR and GPs are projected to receive $7 million in carry with a detailed 10-year projection schedule. I have the granularity to account for any changes in fund structure and account for its exact impact on value. I can even find a sturdy and defensible valuation at significantly lower than the previous OPM outputs.

By contrast, using the DCF method, we come up with $1.8 million to $2.0 million, a much narrower range and more optimal for estate planning purposes.

Planning Opportunity

Carried interest presents a huge estate planning opportunity for any of your clients who are compensated with it. However, the process is complex and requires the insight of an appraiser and attorney with relevant experience. In part two of this series, we will expand further on opportunities with carried interest derivatives.

Anthony Venette, CPA/ABV is a Senior Manager, Business Valuation & Advisory, DeJoy & Co., CPAs & Advisors in Rochester, New York. He provides business valuation and advisory services to corporate and individual clients of DeJoy.